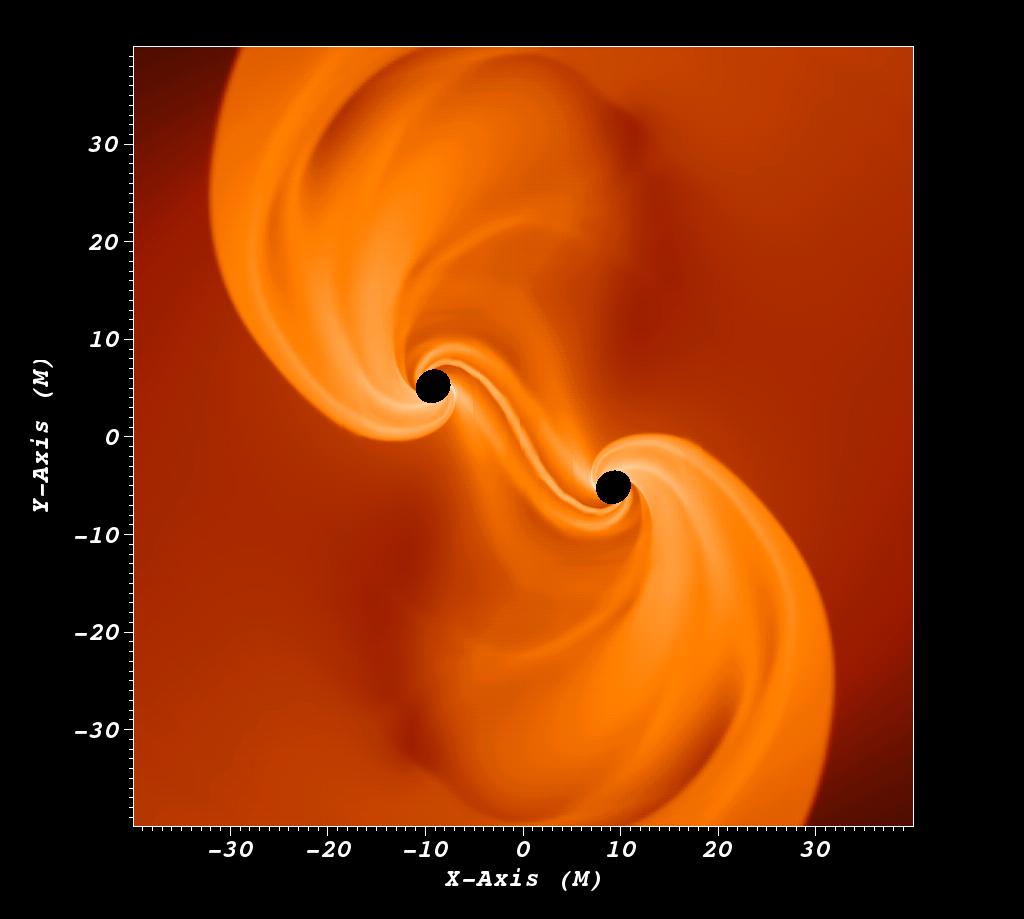

Supermassive stars are hypothetical objects with masses between 10,000 and 1e8 solar masses that are kept in hydrostatic equilibrium by radiation pressure (unlike ordinary main sequence stars that are powered by nuclear fusion). Even though such a star has never been observed, they are hypothesized to have existed in the very early Universe at high redshifts when the first stars and galaxies have formed (an era of the Universe that is not yet accessible to telescopes). The collapse of supermassive stars is a possible way of explaining the puzzling existence of supermassive BHs at those high redshifts (z > 7). Recently, I have shown that it is possible to form a merging BBH system during the collapse of a single supermassive star. The formation of two BHs is made possible by a non-axisymmetric instability encountered by rapidly rotating and radiation pressure dominated collapsing stars that leads to fragmentation. Electron-positron pair creation at high temperatures above 10^9 K causes further loss of pressure, and accelerates the collapse in each fluid fragment, eventually forming an event horizon around each fragment. Since the formation of a pair of BHs from just one supermassive star gives rise to very powerful gravitational radiation that can be seen from the edge of our universe with space-borne GW observatories, an observed GW signal may inform cosmology about the possible formation processes of supermassive BHs when the universe was less than 1 Gyr old. This particular work led to a press release that was picked up by newspapers and popular science magazines around the world (see here).

The corresponding publication has been published in Physical Review Letters, and was highlighted as a Physics Synopsis.